大概在初中后期或高一前期,我对装半导体收音机开始感兴趣。最早是非常简单的“矿石”收音机。就一根天线,大约1毫米或0.5毫米左右的漆包铜丝(漆包线),3-5米长,通到室外。另一头接一个二极管。二极管的另一头接上耳机,耳机的另一头接到”地线”。这样简单的装置就可以听到当地的广播电台了!当然声音是非常的弱。

后来的几年中我逐步装了几个稍微“高级”一点的晶体管收音机,有四管的,有六管的。这些收音机少的可收到4-5个台,多的可以有10多个台,包括外地的电台。有几件事和人对这个过程有重要的推动作用。一个是我的一个表舅。他是一个无线电专家。我们放暑假时经常去他们家玩。记得有一次去他家,看到他在巴掌大的一块玻璃钎维版上连几个电阻,电容,晶体管,还有线圈,电池,居然就可以收到电视台的音频讯号了!太神奇了!另外我中学班上也有两个同学在装收音机,其中一位也是非常懂行,装收音机的电路已经是非常复杂了。当时好像有《科学普及》及《无线电知识》等杂志也经常介绍这方面的知识,最重要的是都有完整的电路图。记得后来还买了一本《晶体管电路原理》作为参考书。但是其实也只是懂点皮毛。大部分时间是依样画葫芦。

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-136810701-56fd5e545f9b586195c7457c.jpg)

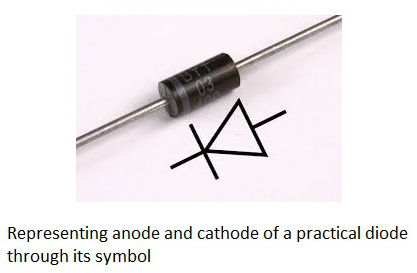

下面是一张维基网上半导体收音机的照片。和我们那时候装的差不多。

By Gisling – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20223436

那时观前街上有一家门面不大的半导体零件商店,两扇玻璃拉门。进门就一个玻璃柜台,10米左右长。里面摆满了各种电子零器件,二极管,三极管,电阻,电容,所有半导体收音机要用的零件都在此可以买到。好像还有现成的印刷线路版(电路都连好了,但没有元器件)。

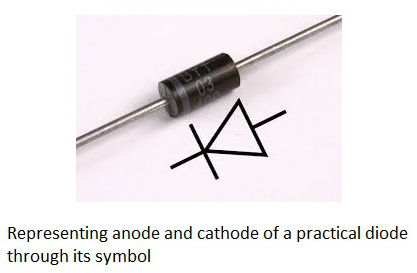

通常的过程是先看了书或杂志,或听别人介绍了,有了个完整的线路图。(上图是一个电路图例子。)然后就去市里各家商店买零件。有时可以买到成套的元器件和电路版,回来只要焊接就可以了。大多数时间是从一块电路板开始。比较好的是玻璃纤维版,稍差一点的是一种层压板, 2-3毫米厚。最简单的电路板是什么都没有的。这时就要设计什么元件放什么地方,线怎么连才能减少或消除交叉线。这个增加很多工作量,但也很有意思,以致后来读拓扑学时有了非常直观的理解。用这样的板还要为插元器件的地方打孔。一般还要在孔上钉上空心铆钉。都是额外的工作。最好用的是印刷电路板,所有线路都连好了,只要把元器件插入预留的地方,焊接就行了。

装好收音机以后调试通常很化功夫。要是装的时候比较仔细,线路没接错,元器件没烫坏,一般装好后,收音机就会“响”,至少可以收到少数几个本地信号强的台。要收到很多台,就要进行精心调制,移动线圈在磁棒上的位置,调节耦合线圈的位置,还有几个可调电阻,电容,等。调好线圈位置后通常要用腊封住线圈,这样可以固定位置。有时候不当心焊接时,电烙铁时间长了,把东西烫坏了(晶体管最容易坏),就很麻烦,很难发现。比较理想的是用个“万用电表”来查,可是那时我没有这个东西。经常是用个耳机搭在不同的地方听,希望能判断哪里出了问题。但这个方法效率和准确率都很低。有时没有办法,只好采用更换零件的方法。

那个年代学校上课不忙,在空余时间装收音机学了很多东西,还是很有意义的。

Assemble Transistor-Based Radios

Sometimes around late junior high and high school years, I became interested in assembling transistor-based radios. One very elementary form of it was a simple “mineral rock” radio (not sure where the name came from, probably because a diode is a piece of semi-conductor). All you need is a long piece of enameled wire as an antenna, maybe 3-5 meters in length and 0.5 to 1 mm in diameter. You lay the wire along the wall, going outside of the house through a window. The other side of the wire connects to one side of a diode. Then diode then connects to one side of an ear-phone. The other side of the ear-phone connects to “ground” which usually is another piece of wire that is stick to the ground somewhere in the house. One could receive the audio signal from a local broadcast station and listen to their voice! Very magic! Usually the audio is very weak, but nevertheless auditable.

In the next a few years, I assembled a number of transistor-based radios, from 4-transistor to 6-transistor of various kinds. These radios can receive as few as 4-5 stations to as many as over 10 stations, including radio stations from other cities. A few people and events influenced me in this endeavor. One is one of my uncles. He is an expert in radio technologies. One time in a family visit, I saw he was able to put together a few transistors, resistors, capacitors, coils, and a piece of battery on a board of the size of a palm. The thing can receive the audio signal of a nearby television station! It was a real magic to me! In addition, at the time, I had two high school classmates who were good at this as well. One of them could assemble very complicated radios already, e.g., one with 8 transistors. I remember there were some popular magazines around time that discuss these technologies and do-it-yourself information, such as “Popular Sciences” and “Knowledge of Radios,” most importantly these magazines often carried complete circuits for radios so the readers can follow them and assemble their own radios. I even bought a book “Principles of Transistor Circuits” a bit later as a reference book. Looking back, I didn’t really quite understand all the details. Most time it was just following the directions and assembled the devices as instructed.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-136810701-56fd5e545f9b586195c7457c.jpg)

The following is a photo of a transistor based radio from Wiki, which looks very similar to what we were doing at the time.

By Gisling – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20223436

There was a small electronic store with two glass doors. There was only one glass counter inside the store, maybe 10 meter long. All kinds of electronic components were on display in their own boxes inside the counter. One can visually inspect these elements from outside the counter. These elements include diode, transistors, resistors, capacitors, anything and everything needed for a transistor radio can be bought here. There were also “printed circuit” board in which the wires are etched (printed), but with no elements on it.

A common process is to read the book or magazine articles, or through others, to get a complete circuit for the radio. (See an example above.) I would then go to various stores across the city to purchase needed items. Sometimes one can buy a complete kit, all needs to be done was to assemble them together, mostly soldering. Usually one starts with a piece of plain board, either fiber based or laminated board, maybe 2-3 mm in thickness. The most primitive board has nothing on it. You’d have to start with a design, where to put everything, how to lay wires with minimum crossing or overlay. This increased quite amount of work. But it was also very interesting, which made a first impression on the science of topology. One would also have to drill holes on this kind of board to host the electronic elements. Usually one would also install an open-shell rivet on these holes so the electronic elements can stand on it when soldering to the board. Those are all extra work. It is best to use some printed circuit board (ready-made board), all wires had been connected. All one needs to do is to install the electronic elements and solder them.

Testing after assembling usually is a time-consuming process. If one was careful during the assembling, no mistakes were made in connecting various elements, no components were burnt, usually the assembled radio would work in a primitive stage, meaning it may be able to receive a few local stations with strong singles. But if you wanted to make it work better, in a more optimized condition, careful adjustments were usually necessary, including position the coil on the magnetic bar (as the antenna), coupling level of the other coils, adjustable resistors and capacitors, etc. After the positions of the coils were set in a good position, one would often use wax to fix the positions so the coils won’t move away from the optimized positions. Sometimes some components, especially the transistors would be damaged by burning, usually due to long iron time in soldering, this would create a radio that doesn’t work. It is very hard to find this type of problems, as visual inspection wouldn’t find any problems. The best approach would be to use a multi-meter to find the problems. But I didn’t own a multi-meter at the time (it was an “expensive” item.) In these cases, I’d have to use some ear-phone to listen to various places on the circuits, using the noise heard through the ear-phone to help detect the bad components or connections. This was extremely inefficient and inaccurate. Sometimes one just had to resort to the replacement of certain suspicious components.

Those years, the school wasn’t busy. I was very happy that I was able to learn the basics of transistor-based radios and was able to put together a few that I could actually listen to. It was very meaningful.

Leave a Reply